hello all!

A few updates:

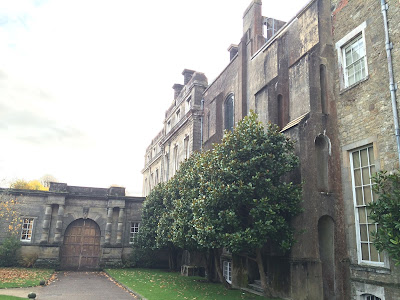

- I'm currently working on some corrections for a chapter for a book called Museums and Activism, edited by Richard Sandell and Robert Janes. I'm so excited to be part of this, and have really enjoyed writing about Sutton House outside the context/confines of a thesis.

- I'm also working on some illustrations relating to the history of Sutton House. I'm not sure what I'm going to do with them yet, but I'm feeling a self published book or a zine coming on... I might share some of those on this blog soon.

- Most significantly, I'm delighted to have been appointed as a part time Lecturer for the Museums and Galleries in Education MA at the UCL Institute of Education. It's the MA I did in 2010-2012 and the department within which I've been doing my PhD, so it's really great to have the opportunity to contribute to a department that has been so supportive, inspiring and rewarding. I will start in the new year, and Sutton House have been super accommodating, so I will be continuing my work there too.

For my interview I was asked to give a presentation about diversity in museums and galleries. It ended up, like a lot of my writing, more of a polemic than I had intended. I thought I'd share some of the thoughts I raised in my presentation here (in more form) as I thought it might be of interest to some.

Speaking about diversity in museums, you have to start with the staff. Museum Studies MAs and other post graduate qualifications are inherently a barrier. Increasingly museum jobs are requiring a postgraduate qualification, or otherwise a lot of experience which usually means unpaid work. This is, of course, a class barrier, which in turn is a barrier for people of colour, people with disabilities and a large portion of the LGBTQ community. Museum Studies MAs are unsurprisingly reflective of the wider heritage sector and the education sector in that it comprises mostly white, middle class women.

Andrea Fraser notes that the majority of people of colour working in museums (in the US) are security staff or catering staff, and do not hold the more “professionalised” roles related to curation, collection care/conservation or education. This is also reflective of UK museums as well. I would urge museum professionals recruiting staff to consider whether or not a post graduate qualification genuinely is essential, and I imagine the answer is almost always no. A more diverse workforce might be built if transferable skills from other jobs are considered as highly as post graduate qualifications or masses of voluntary experience within museums. Having time and capacity to volunteer is a huge privilege, and requires that candidates have sufficient savings or financial support to be able to do it.

I also think we need to be wary about the overuse or rather misuse of the word diversity. And more specifically we should be wary of assuming there’s a commonly understood definition. I think that in museums, diversity is usually a lazy shorthand for people of colour. This often reductive term neglects other protected characteristics and issues of class, and access in terms of disability and mental health. It also often fails to address intersectional identities: some trans women are Muslim, some black people are disabled, some autistic people are refugees etc etc etc.

The first obstacle in addressing the diversity problems in museums is that we all need to start acknowledging our privileges more. People often don’t like to be called out on their privilege or their complicity with ableism, heteronormativity and white supremacy. Linked to this, it is often difficult to articulate to people with privilege, what it’s like to be oppressed, marginalised, or invisible- when we introduced gender neutral toilets at Sutton House for example, some people couldn’t understand why it was worth doing. We had a young trans teenager who visited who, along with their mother, told us it was great to find somewhere where they felt safe and welcome. Cis people who have never felt vulnerable in a public toilet, or had to go without using a toilet in a public space because there was no where to accommodate them, might not be able to see why such a small change can be such a crucial one. I myself have had experiences where I’ve been reminded of my blindness to barriers faced by other marginalised people. During my exhibition

126, some disabled participants were rightly disappointed that they had contributed to the exhibition, but that it would be exhibited in a place inaccessible by wheelchair. I felt bad, but it wasn’t about me, we have to listen, get over our own bruised ego, and make changes to our behaviour.

Museums, and their staff, need to be good allies. Saying ‘we welcome all’ is not being an ally, what are you doing about it? How are you reducing the barriers faced by people of colour, who only see white faces in the museum? How are you making concessions in pay for entry museums for local working class visitors who can’t otherwise afford the fee? How are you challenging heteronormativity in depictions, for example, of the home and family in historic house museums? How are you making school workshops engaging and accessible for children with autism or other specific educational needs? How are you developing alternatives to audio tours for deaf people?

The Morris Hargreaves McIntyre ‘spectrum of audience engagement’ (

see page 19 here), which is something I return to regularly is a good measuring tool for museums, or an aid for museum studies students to assess museums they encounter: where do they fit, where are they aiming for? My aspiration is always to achieve the final column: museum as a platform for ideas, as an “egalitarian facilitator”. A key word there is Safe Space, it’s not only about producing programming and exhibitions to appeal to marginalised groups, but to steer a cultural change that makes museums a space of an exchange of ideas and expertise between visitors and so-called “experts”.

Likewise, establishing trust with communities as an “egalitarian facilitator” means that marginalised communities are also more likely to visit and engage outside of programmes directly marketed towards them. If you invest time and resources into a community, that community are more likely to feel welcome, and that the museum is a space for them.

Sutton House Queered, the year long LGBTQ programme of events and exhibitions at Sutton House is, I’m pleased (and a bit smug to say) a good example of this. At the beginning of the project we set out to make Sutton House a safe and welcoming place for the LGBTQ community, for this year and beyond. We were approached by the Fringe Queer Film Festival to host one of their biggest events, a screening of the film

Out of this world and a Q&A with Mykki Blanco. They approached us based on the reputation we have established over the year, the curator of the festival had been to a few of our events and knew that we were serious, and not taking a tokenistic approach to our LGBTQ engagement. This impact, and the relationships built on the back of it, influences the legacy of such projects once key milestone anniversaries, such as the 50 year anniversary of the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in England and Wales, have ended.

Exhibitions that are built for, with and by communities, is an ethos I bang on about quite regularly. This often means conceding that museums professionals aren’t the experts, and that unsettles a culture of gate keeping and ivory tower syndrome, which museums are still often regarded as being inflicted with.

I attended the 13th LGBTQ History and Archives conference at the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) a few weekends ago. As usual it was great. Steven Dryden who was one of the curators of the British Library exhibition

Gay UK: Love, Law and Legacy, told us that they welcomed 88,502 visitors over three months, this was 111% over target, the second most visited exhibition of the year, 6th best attended in the space- most of which had a much longer run time. These are the sorts of figures that make the museum big wigs who might question the desire for such exhibitions sit up and take notice. This has given the newly formed British Library LGBTQ network extra mileage and perhaps lobbying leverage to make demands for further work, and they have created new guidelines to say that every exhibition must have an element relating to LGBTQ history, be it an object, some interpretation, an online blog post etc. This in turn has implications for future collection building too.

We must also start to challenge the assumption of a shared understanding of what is ‘important’, particularly in regards to historic houses and other heritage sites. They are usually deemed heritage sites because they are considered ‘important’. But what does important mean? Usually it means related to the monarchy, an aristocratic family or a well known successful figure, or of architectural significance. If we reframe what constitutes “importance” in public history, we open up a wider and more exciting variety of spaces. Sutton House was dismissed by architectural historian James Lees-Milne, whose influence likely saw it sit in a state of decay for almost 50 years. ‘No more important’ than any other house he wrote in his diaries. Its true importance came to be in its potential, rather than its past, its potential for a community space for the people of Hackney. The

Birmingham Back to Backs are another great example. They were far from unique, thousands were built in inner city areas to accommodate for a burgeoning population growth in industrial areas. These homes were occupied by normal working people, a vision of history much more relatable to most visitors and potential visitors than the grand crumbling piles owned by Lord and Lady Upperclass.

The conference at the LMA was about oral histories, and was called ‘Talking Back’, a title inspired by bell hooks, who was raised to believe that to talk back was to challenge or stand up to an authority figure. This idea lends itself naturally to oral histories, but also, I’d argue, to museums in general. If we think of the museum as the authority figure, then people within marginalised communities must ‘talk back’ to be heard, seen and recognised. Bell hooks said: ‘It is in the act of speech, of “talking back”, that is no mere gesture of empty words, that it is the expression of our movement from object to subject- the liberated voice’. It’s our responsibility, as people in the museum sector, not to idly wait until the oppressed, forgotten and ignored ‘talk back’ to us, but to actively invite them to do so and to listen to them.

(Apologies these are only half-formed thoughts, and no doubt full of typos, but that’s part of the charm of blogging... isn't it?)

In 1948 Peggy Guggenheim’s collection was

exhibited at the 24th Venice Biennale in the Pavilion of Greece. To

mark the 70th anniversary of the exhibition, 1948 La Biennale di Peggy Guggenheim in the Project Rooms at the

Guggenheim, Venice, revisits the career-defining Pavilion display; its origins,

construction and curation. Billed as ‘an homage’, the exhibition does not

attempt to further examine the artworks that featured in the original, but

rather gives an inside look into the behind the scenes work that led to the

first postwar display of a modern art collection in Italy following 20 years of

dictatorial regime.

In 1948 Peggy Guggenheim’s collection was

exhibited at the 24th Venice Biennale in the Pavilion of Greece. To

mark the 70th anniversary of the exhibition, 1948 La Biennale di Peggy Guggenheim in the Project Rooms at the

Guggenheim, Venice, revisits the career-defining Pavilion display; its origins,

construction and curation. Billed as ‘an homage’, the exhibition does not

attempt to further examine the artworks that featured in the original, but

rather gives an inside look into the behind the scenes work that led to the

first postwar display of a modern art collection in Italy following 20 years of

dictatorial regime.

While visually the audience is taken back to

1948, the exhibition perhaps lacks in giving sufficient wider context of the

world that the Greek Pavilion exhibition took place in. Greece was in the midst

of a bloody civil war, and fascist dictator and former Italian Prime Minister

Mussolini had been dead for just three short years. The impact of Peggy

Guggenheim’s diverse and forward-looking collection being a centrepiece of the

Biennale that year is lessened when removed from its context. Further

exploration of world events beyond the exhibition and its pavilion could have

strengthened the narrative and provided further insight into Peggy’s character.

While visually the audience is taken back to

1948, the exhibition perhaps lacks in giving sufficient wider context of the

world that the Greek Pavilion exhibition took place in. Greece was in the midst

of a bloody civil war, and fascist dictator and former Italian Prime Minister

Mussolini had been dead for just three short years. The impact of Peggy

Guggenheim’s diverse and forward-looking collection being a centrepiece of the

Biennale that year is lessened when removed from its context. Further

exploration of world events beyond the exhibition and its pavilion could have

strengthened the narrative and provided further insight into Peggy’s character.